What’s in the Book?

Twelve Guiding Principles

The 12 Guiding Principles include successful approaches and strategies for communication and facilitation, conflict resolution, negotiation, managing and facilitating multiparty stakeholder processes, adaptive management, managing complexity, participatory decision making, building local community capital, and many other local community leadership and management skills.

Notes from the Field

‘Notes From the Field’ are presented at the end of each chapter, they provide practical Dos and Don’ts which is a list of suggestions or “best practices” for applying the guiding principles discussed.

The Case Studies

The Case Studies share specific and effective approaches on how communities are moving from struggling towards thriving, including those from locations that have local economies considered developing, transitional, or developed, in the US and other parts of the world. They also highlight other principles that were involved.

Research Corner

‘Research Corner’ outlines five unique characteristics or criteria that adequately describe each principle plus related research. They are featured in the introductory section of every chapter.

“I hope this book will provide you with the practical leadership and practitioner tools that are needed on your journey of supporting the health and vitality of your local community.” - James S. Gruber (the photo to the right was taken in Kinsasha, Democratic Republic of Congo)

The Twelve Guiding Principles

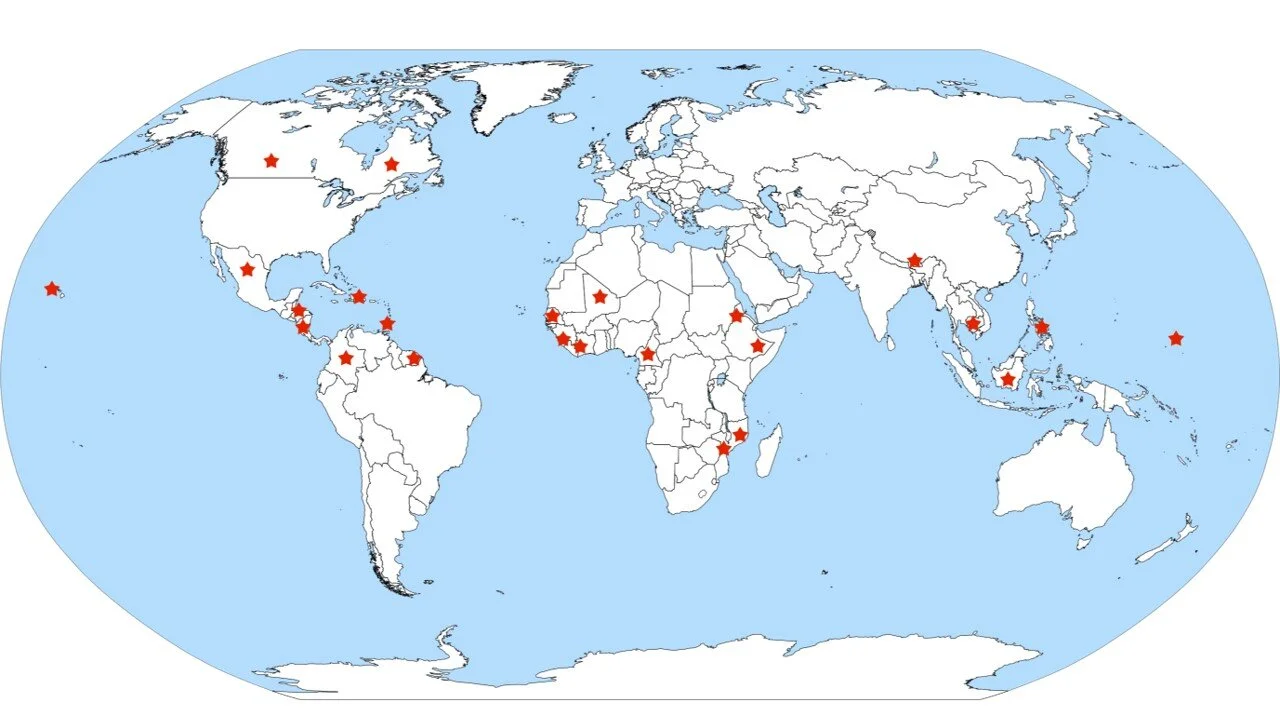

These 12 guiding principles are based on research with data from 27 countries in five continents (see map on the right). I had an opportunity to listen to and read what local practitioners, local community leaders, and researchers found to be common in many, if not most, communities that were healthy and thriving, or at least beginning to thrive. The initial data was available from a workshop facilitated by the late Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom.[i] I had the opportunity to sort through all this information, which included hundreds of case studies from the workshop, as well as academic research papers and some site visits, and then organize the findings into these 12 categories that are the 12 guiding principles (shown below).

[i]. Elinor Ostrom facilitated this 1998 World Bank Foundation Workshop.

Map of Research Sites

Excerpts from Case Studies

Brief excerpts from three case studies are provided below. The first two case studies are available to read in full under the “Full Case Studies” tab.

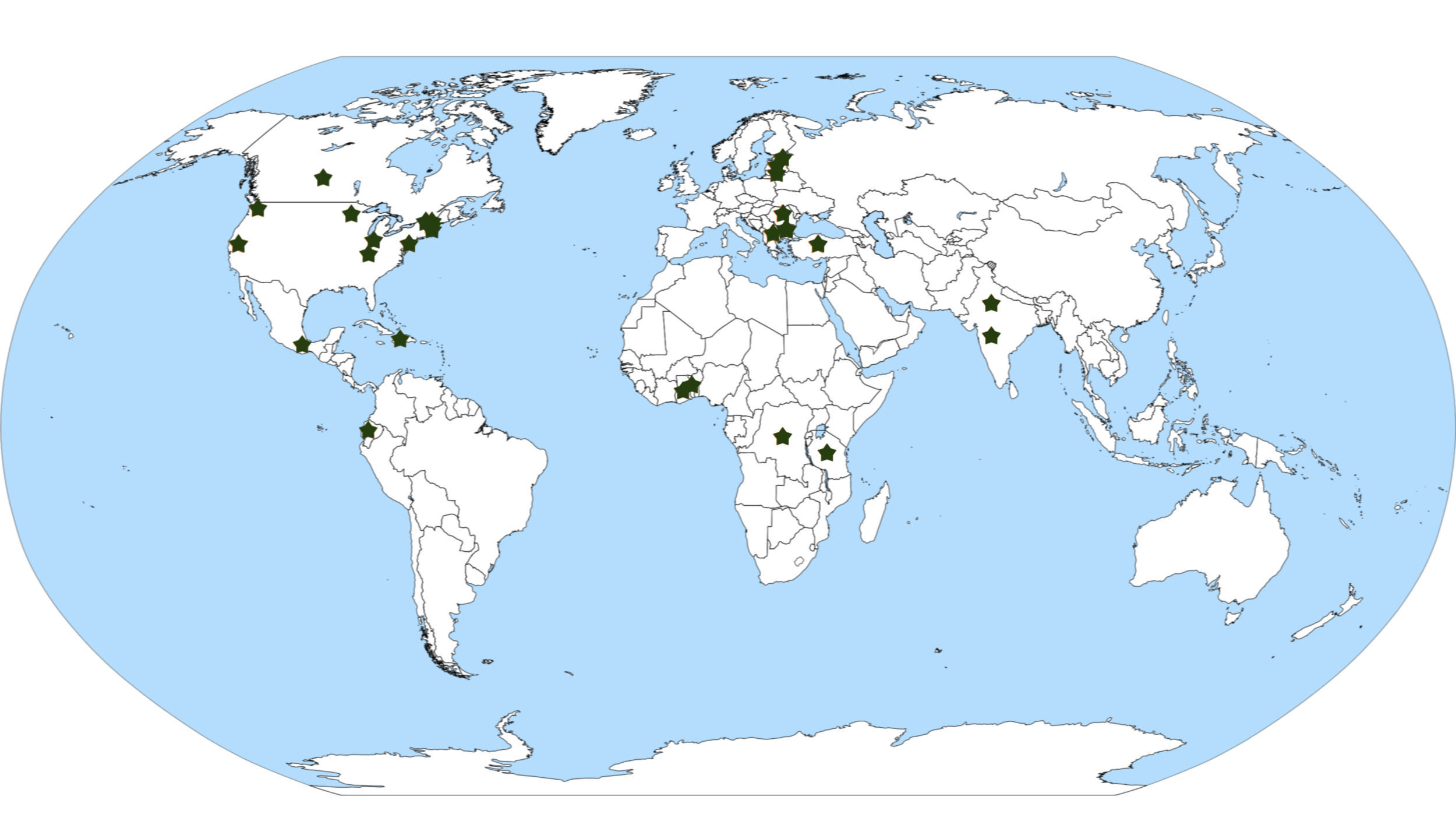

Map showing the locations of the 44 sites of case studies and brief examples in the Book.

Example 1:

Climate Change and the Minnehaha Creek Watershed: Where Will All the Water Go?

Minnesota, USA

Prologue

This is a story of how an urban area come together to figure out what to do with all that rain. Climate change was already affecting this south-central region of Minnesota and needed to be addressed. The Minnehaha Creek Watershed District was a key local partner in this multi-stakeholder process. Rather than hiring experts to design and build additional “grey” (concrete) infrastructure, the watershed district worked with local governments, NGOs, universities, and others to engage a wide range of stakeholders in coming together and developing an integrated, comprehensive approach. Outcomes included changes in land use and planning approaches, promoting low impact development with less impervious areas, encouraging rain gardens, enhancing storm water retention through “green” infrastructure, addressing educational needs, and developing strategies for sustainable financing of new stormwater systems through impact fees on impervious surfaces.

Photos from the Minnesota case study

Example 2:

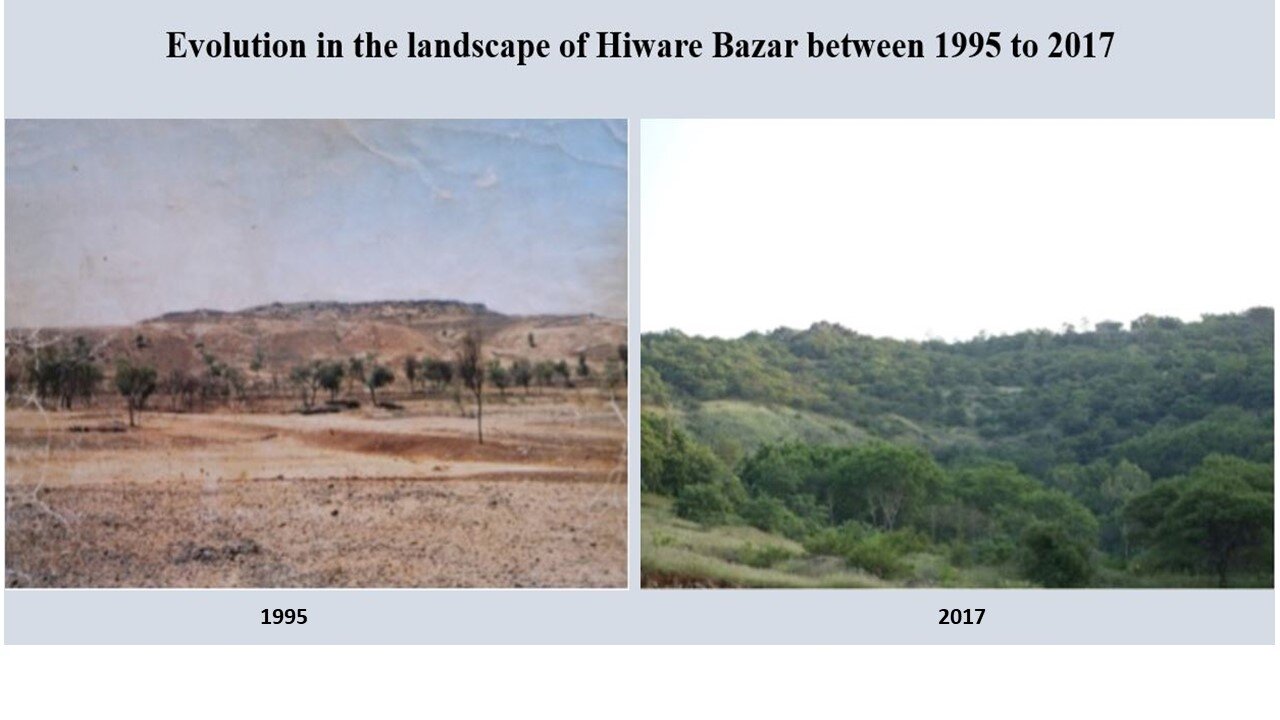

Regenerating a Village’s Land and Water Resources Water-led Transformation,

Hiware Bazar, India

Prologue

Hiware Bazar, one of India’s most prosperous villages, was transformed from a drought-prone and water-scarce settlement to an economically strong community. The fate of the village changed in the 1990s, after a young Popatrao Baguji Pawar, the area’s only postgraduate, was elected village head. Pawar engaged residents in planning and execution of various projects, including watershed management, building of percolation tanks, and carrying out extensive plantation drives. He realised that there was a need not only to address drought-related issues but also to make residents self-reliant, and persuade them to participate in development work to help bring about social, economic and environmental change. The story of transformation that is Hiware Bazar illuminates how effective communication by a local leader brought residents together to address environmental challenges, paving the way to economic prosperity and social development – and, thus, a healthier future.

Photos from the Hiware Bazar case study

Example 3:

Reclaiming Wood, Bricks, Lives, and a Community

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Prologue

This case presents a “multi-faceted approach to solving the complex problems of inner-city vacant homes, unemployment, and the need to protect forests in an age of climate change and can serve as a model for other cities.” In Baltimore, a city with thousands of vacant and abandoned homes, reclaiming wood, bricks, and other valuable materials through deconstruction has been proven to “help remedy problems related to blight and unemployment and contribute to neighborhood revitalization.” This successful community-wide effort to increase environmental, economic, and social benefits, as well as sustainability and resilience, relied on the willingness of a team of partners to face large-scale challenges while engaging in collaborative problem solving. It not only succeeded in recovering valuable and re-useable resources but also resulted in a positive systemic change that improved the lives of local citizens. This case draws upon an interview with key a stakeholder as well as published accounts of this initiative .

This video was created by the Mutual of America Foundation. Press play to learn more about this case study and see why we had to include their incredible story in our book.

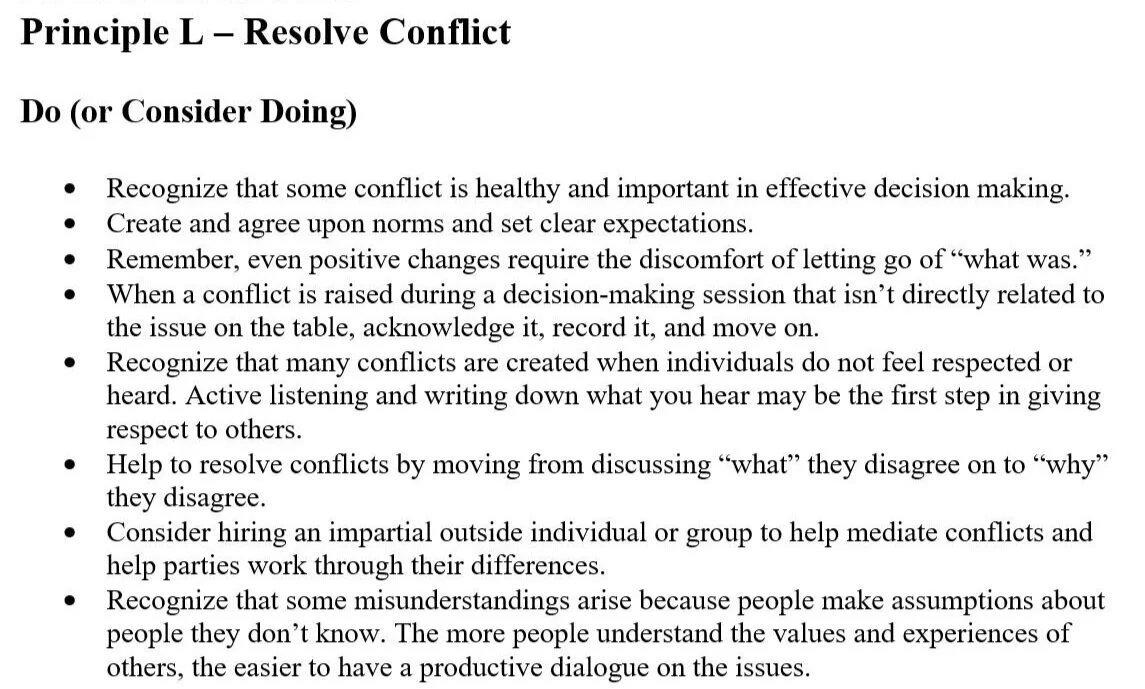

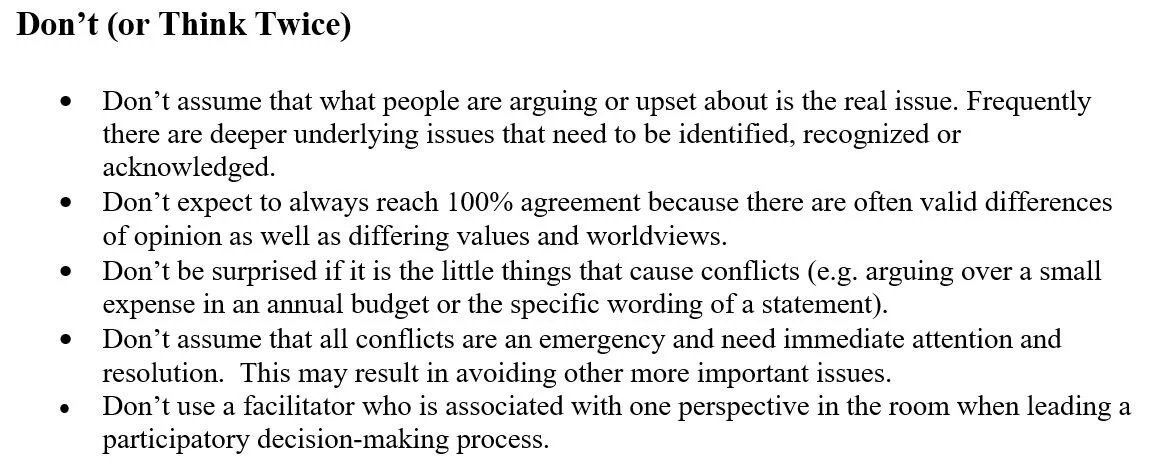

Notes from the Field

Below is an example from one of the Do's and Don'ts sections (from Chapter 13 ) that are part of each chapter

Research Corner

Below is an example of a ‘Research Corner’ that you will find at the beginning of each chapter. The corner introduces each principle using evidence and research from outside sources.

Principle K: Strengthen Enabling Conditions - Five Characteristics

Community has common interests, shared norms, and a relatively healthy local social structure in which divisions are not too serious or disruptive of cooperation.

There are clearly defined boundaries of the community and its resource systems.

While the public is unsatisfied with the status quo, it is not feeling hopeless.

Citizens/stakeholders are willing to participate due to high sense of community and/or dependency on the local natural resources.

There is adequate support and investment of financial and other resources to support transitional costs.

Research shows that community norms strongly influence what community members’ value and beliefs, and what actions they take.[i] It is essential to improve pre-conditions that strengthen the local foundation prior to undertaking a new effort or initiative. This strengthening can reduce challenges and increase the likelihood of success. One precondition is that the community is culturally and/or socially united, or at least is able to work together despite some extent of division. Communities that have a homogenous social structure[ii] common interests, shared norms[iii], and a history of cooperation[iv] are more likely to be able to work together in a multi-stakeholder, consensus building manner. Other pre-conditions that indicate a willingness by individuals to participate in local community initiatives and decision making processes are that community members: 1) value their community, 2) rely on local (human and natural) resources,[v] and 3) are currently unsatisfied with the status quo but do not feel hopeless.[vi] Clearly defined boundaries[vii] and standards that govern and manage community systems are also an important pre- or early condition for enhancing the likelihood of future success. If most of these indicators of a strong foundation are present, it signals that the community is ready to begin the change process that will enhance their future health and vitality.

However, it is often the case that some of these enabling conditions are inadequate or too weak to take on a challenging initiative. If this is indeed the case, the initial work of the community needs to focus on strengthening their social foundation, which includes forming positive social norms. A booklet titled “Promoting Positive Community Norms”[viii] provides sound ideas on how to grow and promote positive community norms. Other areas that may need to be addressed may include resolving conflicts and securing adequate resources to undertake the initial steps for moving forward.

Endnotes:

[i] Thomas A. Heberlein, Navigating Environmental Attitudes (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012), Chapter 6.

[ii] Paul M. Thompson, Parvin Sultana and Nurul Islam, “Lessons from Community-based Management of Floodplain Fisheries in Bangladesh,” Journal of Environmental Management 69 (2003): 307–321.

[iii] Arun Agrawal and Clark C. Gibson, “Enchantment and Disenchantment: The Role of the Community in Natural Resource Conservation” World Development 27, no. 4 (1999): 629-649.

[iv] Ruth Meinzen-Dick and Anna Knox, “Collective Action, Property Rights, and Devolution of Natural Resource Management: A Conceptual Framework” International Food Policy and Research Institute (Capri Working Paper no. 11, Vision Initiative, 1999).

[v] Brooke A. Zanetell and Barbara A. Knuth, “Participation Rhetoric or Community-Based Management Reality? Influences on Willingness to Participate in a Venezuelan Freshwater Fishery,” World Development 32, no. 5 (2004): 793-807, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.01.002.

[vi]Denise Scheberle, “Moving Toward Community-Based Environmental Management,” American Behavioral Scientist 44, no. 4 (2000): 564-578, https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640021956387.

[vii] John M. Anderies, Marco A. Janssen, and Elinor Ostrom, “A Framework to Analyze the Robustness of Social-ecological Systems,” Ecology and Society, vol. 9, no. 1 (2004): 18 [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss1/art18/; Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.19.

[viii] Jeff Linkenbach and Jay Otto, Center for Disease Control. CDC’s Essentials for Childhood: Steps to Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and Environment, accessed June 20, 2019, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/51c386a4e4b0c275d0a5bbf2/t/58e7b96dff7c5020c21121b5/1491581302087/INTRO+TO+POSITIVE+COMMUNITY+NORMS.pdf.